Friendship With A Foreign Student: A Guide for Host Families and Friends of Foreign Students – NAFSA: Association of International Educators

Congratulations!

Congratulations on your decision to host an international student! This is the start of what could be a lifelong relationship where you and your student will learn from each other and grow together. The rewards are great- from expanding each other’s understanding of the world and sharing that new understanding with others, to discovering a new and valuable friend. Many people host international students because of their own experiences oversees while others host because they are simply interested in learning about others. We hope that this experience will encourage you to break stereotypes, discover your own city, and continue the international experience once your student returns to his or her home country. Hosting is a small but essential step in contributing to world peace, tolerance, and understanding- it happens one relationship at a time.

Across The Globe

People from across the globe are more mobile than ever before. Consequently, the number of students and scholars attending college and universities outside of their home countries has been continually rising. More than 565,000 students were enrolled in U.S. academic institutions in 2005. The presence of foreign students and scholars on U.S. campuses and in nearby communities offers unique opportunities for cross-cultural learning and for building personal ties between Americans and people from other nations. The reason they choose to study in the United States vary as much as the students themselves. Oftentimes, it is for the opportunity to learn a language in which they plan to conduct business in the future. Other reasons include research opportunities, training in areas that are more advanced in the host counties, personal interest in living abroad, quality of education or technology, and more.

Introducing Students to Other Cultures

As a host, it is important to remember that your student’s first priority is academic studies. While students must maintain their immigration status, which depends on their responsibilities at school, the majority would like to expand their experience and learn about the lives of those in the host country. They often want to become immersed in the host culture as much as possible during their time here, and there is much to be learned outside of the classroom.

Discovering features of other cultures is amazing! Some aspects of U.S. culture that you can introduce to the international students you host are:

-

Social Relationships: While Americans may be open and friendly, it can take time to develop actual friendships. International students are often discouraged that making friends isn’t as easy as they thought it would be. Some international students have commented that they feel Americans are insincere. Mistaking American friendliness for friendship, they are disappointed when relationships do not take on a deeper meaning. In many other cultures, friendship is reserved for a very few people, is based on mutual love and respect, and involves unlimited obligation. In the United States, close friendships certainly exist, but Americans also have many “friends,” among whom the foreign student may be only one. Talking about how friendships develop in the Unties States may help the student achieve a realistic view of what can be expected of his or her American friends.

-

Achievement: In the United States, status is primarily based on what individuals have achieved on their own, including education, and the level; of success in their employment. Many students’ cultures dictate that respect is given based on other factors such as age or title. Additionally, some international students may not be used to the high level of competition in the United States.

-

Informality: The U.S. lifestyle is generally quite casual, and this can be shocking to some students who are accustomed to a more formal structure. Some international students may find it unusual in the beginning to use first names and dress casually.

-

Individualism: Americans are encouraged at an early age to develop and pursue their own goals. There is a higher value places on self-reliance than in many other countries where parents or families help with decision making. In many countries, being part of a group is more important than focusing on the individual. Privacy: The United States on the outside appears to be open and transparent with open homes and office doors. However, Americans enjoy time alone., Value private space, and are guarded with what they consider personal information. International students can have difficulty adjusting to this, especially if they are living in residence halls and share a room with an American.

-

Time: Americans take pride in using their time wisely, which is why they tend to plan events in advance. Punctuality is valued in the United States and this can be a major culture; adjustment to many. Americans may “live by the clock,” but this is not true in many other cultures. In some places, for example, the time noted on a social invitation implies one should arrive an hour or more later. In others, an invitation is extended several times before it is accepted.

-

Equality: International students are often used to a hierarchical system or one in which genders are treated differently. It is important for international students to know that in the United States everyone is supposed to have equal opportunities and has the same rights as everyone else.

While there are many more areas that are culturally different, we encourage you to discover and learn from them. For a successful relationship with your student, it is important to be able to discuss these differences and understand each other’s perspectives.

Expectations

A student may have some expectations of you, including phoning regularly and being in steady contact with him/her. Also, a student may hope to spend traditional holidays with you, especially if his/her residence hall closes during a holiday break. Having a conversation about what you hope to provide and what the student expects out of the relationship is recommended.

What You Can Do

Remember to not change your ways too much to accommodate your student- s/he is here to learn about U.S. culture and fully experiencing it. While it is thoughtful for you to want to prepare meals from the student’s home country or introduce your student to people from the same country, keep in mind that the student is participating in the hosting program to learn the customs and cultures of the Unites States from you.

Before meeting the student, try to become familiar with his or her country: location and size, form of government, the capital and other major cities, major religions, and holidays.

Information about the country may provide clues to the student’s cultural background. Although it is impossible to become familiar with all the cultural differences, be aware that major differences are likely to exist. The student will be your best resource for learning about his or her culture and many stimulating discussions can occur as you explore cultural differences together.

Try not to let previous generalizations or stereotypes you may have heard about the student’s country affect your attitudes. If you have questions about the country or culture that you do not understand, you might ask the student for his/her views; what you learn from a “direct source” may be very different from other perspectives.

Just as differences in customs and culture stimulate conversation, so do explorations of world events and how they are viewed from differing perspectives. While neither we, as Americans, nor the foreign students are necessarily experts on the positions taken by our respective governments, we can learn a great deal by discussing what lies behind the government actions and how we, as individuals, view particular events.

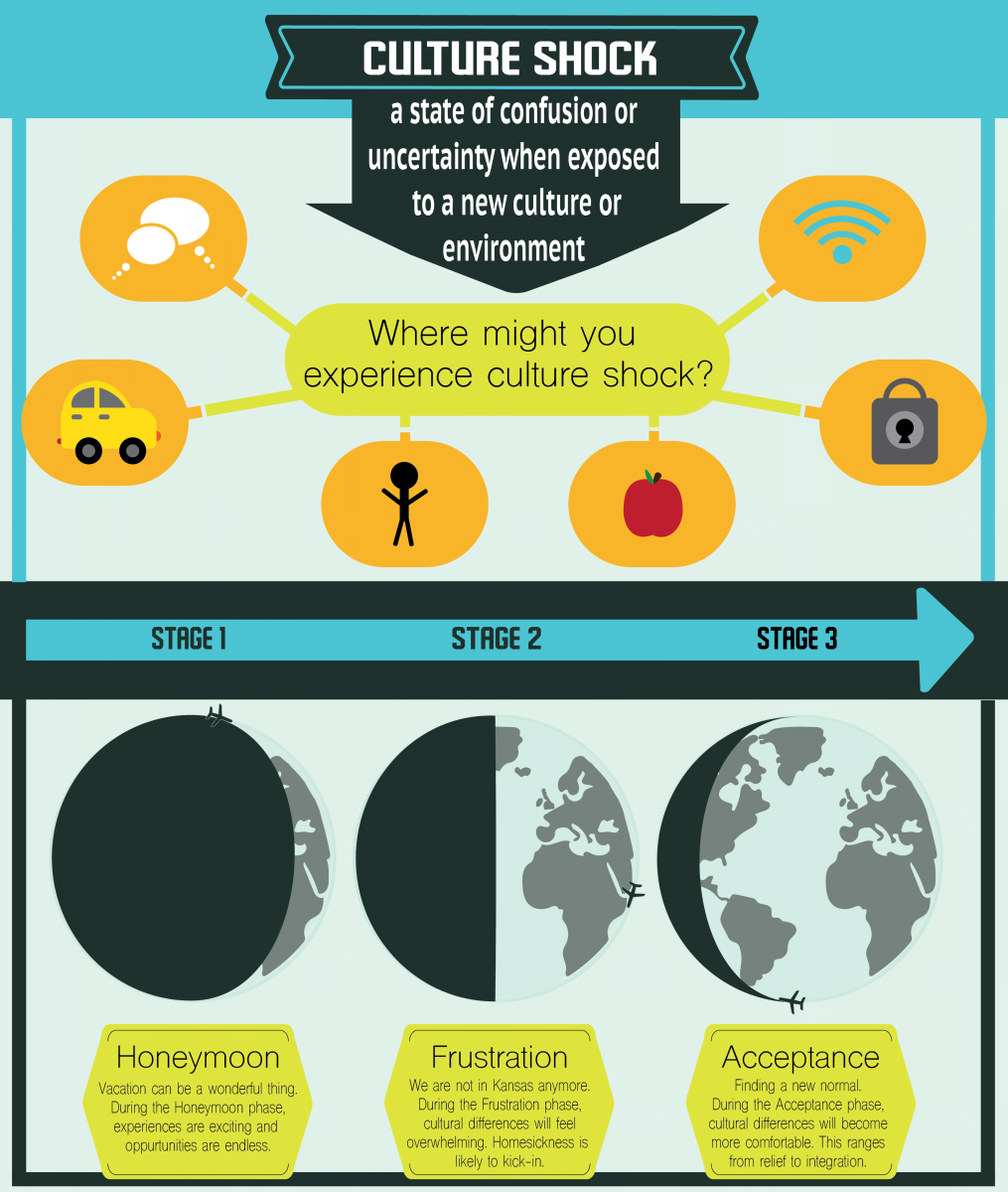

Culture Shock

Many students experience culture shock while living in another country. Adjustment to a new culture and environment is not accomplished in a few days; it can take a year or more. People who enter a new culture almost inevitably suffer from disorientation. The physical and social environment contains much that us new and hard to understand. It takes time to learn how to get around, do laundry, buy food and other necessities, and become comfortable with the new society. It is exhausting and difficult to speak in a second language, understand the meanings that lie behind the spoken and nonverbal language, and learn new behavior.

Below is a graph that illustrates the various stages of culture shock that your student may experience. Some students experience culture shock more severely that others and as a host, it may help for you to understand the stages that your student may be experiencing. Contacting your student during periods where s/he may feel unmotivated or sad is always appreciated and can make a positive difference in his/her life.

Stages of Culture Shock

-

Honeymoon: Upon arrival in the new country, students are excited and eager to learn about their new home. Typically, this stage is relatively short.

-

Culture Shock: As your student settles in to daily life, the novelty and excitement wear off, and your student may start feeling sad or unsatisfied.

-

Recovery: Once your student’s new life becomes more familiar and s/he is more comfortable with living in the United States, your student will be happier.

-

Adjustment: At this final stage abroad, your student has learned to live in a new country and integrates his/her beliefs and lifestyle choices.

-

Reverse Culture Shock: Your student will experience many of the same ups and downs when s/he returns home. Students appreciate staying in touch with heir hosts to have someone to talk about this experience.

-

Reintegration: Your student will learn to adjust his/her new perspectives into the home country’s environment and eventually feel comfortable at how the experience abroad fits in at home.

Symptoms of Culture Shock

As a host, you may want to be aware of certain symptoms of culture shock. If you notice any of these indications in your student, you may want to talk it out with your student or inform the international student advisor.

-

Excitement, and stimulation

-

Confusion, irritability, or withdrawal

-

Sudden intense feeling of loyalty to home culture

-

Physical reactions such as appetite change or headaches

-

Depression, boredom, or lack of motivation

-

Marital or relationship stress

First Steps

Some programs allow for hosts to choose a student based on home country; if you have a certain country of interest, be sure to ask if you can become a host to a student from there or the region. Once you have been connected o your student from the local organization or international student adviser, you will want to contact him or her. Often, the first visit is a meal, or an afternoon or evening conversation. Include suggestions on where to meet and when, how long the meeting is expected to last, and any relevant information about transportation. Also, don’t be surprised or upset if your guest is late; remember that the student may still be getting adjusted to a different attitude towards time.

Students can be lonely, especially when they first arrive in this country, and they may enjoy talking about their family and friends. If you have children, include them in the conversation. Students often enjoy children because they are easier to converse with and may “substitute” for brother or sisters at home. It is important to keep in touch with the student so he or she feels wanted and accepted. A brief note, phone call, or birthday card can help remind the student that, even if you haven’t seen each other for a while, he or she has not been forgotten. In time, students create a new life here, and feelings of loneliness and uncertainty abate.

Ask the student what name you should use when addressing him or her. It may take practice tp pronounce some names correctly. You will want to tell the student how to address you and your family members as well. Learning a few words of greeting in the student’s language can be fun and is always appreciated.

Be sure to explain house rules and procedures (such as typical family expectations regarding use of the bathroom) because some things will be very different from the student’s home country. Encourage the student to ask questions if anything is unclear.

Meals with Your Student

If you invite your student over to your home for a meal, you will want to consider the following items:

-

Does you student have nay dietary restrictions? Many religions restrict certain foods or your student may be a vegetarian, and you will want to accommodate that. If it is difficult for you to do so, a restaurant is also a good option.

-

In many cultures, quests are offered coffee, tea, or a cool drink as soon as they arrive. If your custom is to serve beer or cocktails, it is important to have nonalcoholic beverages available for those whose religion or culture discourages the use of alcohol.

-

Many hosts find that chicken is a “safe” meat to serve and that rice is a good choice because it is a staple in many countries. Fruit juice, soft drinks, tea, or water are usually preferred to milk, which is rarely served to adults in other countries. Rich desserts, for which many Americans have a special fondness, are often unknown abroad and your guest may prefer a piece of fruit or simply a cup of tea at the end of a meal.

-

If you start your meal with a prayer, you will want to explain this custom to your student.

-

Your guest may be quiet during the meal; this may reflect cultural patters from home, or possibly just shyness or nervousness. This is not necessarily a sign that your student is unhappy.

-

Many foreign students are not accustomed to having pets inside the home. Until you know how the student will react, it is advisable to keep pets at a distance.

-

You may want to invite more than one student over as that often allows the student to be more comfortable.

Activities With Your Student

During the first meeting with your student, take time to discover what s/he is interested in doing while in the United States. Perhaps your student wants to attend a local sports game, celebrate domestic holidays like Halloween or Thanksgiving, experience local outdoor activities, etc. You can think about some future activities you can do with your student.

Initial activities might include teaching your student how to use the local bus system. You can also orient your student to the city and perhaps take him/her to a food store that suits his/her needs. Your student may also ask for assistance in renting an apartment and getting settled in. Simply taking them around shops where they can acquire basic items to get started is fun and very helpful. Keep in mind that students come from various financial backgrounds and try not to exceed your student’s limits.

Students may be reluctant to accept invitations during busy school periods, so do not be disappointed if the student must decline in favor of a test or a term paper. Make it clear that he or she is not obligated to accept every invitation and can turn down an invitation when it interferes with academic schedules.

Including the students in as much of your life as you are comfortable with is rewarding. Some hosts invite their students to attend religious services with them. (Students may also invite hosts to a religious service to share their religion.) It is especially important to explain the event to the student if it will be religious in nature and allow them to decline if they are not comfortable with it. Religious tolerance is an essential element in hosting and it is hoped that all hosts and student will respect each other’s beliefs. One way to show respect is to show interest in your student’s beliefs and listen as s/he shares. Don’t try to change a student’s beliefs.

If you have previously hosted another exchange student, try to focus on the positives of that experience and avoid making negative comparisons about your current guest based on experiences with another student.

One person at a time, we all can make positive changes to create understanding and destroy stereotypes. Not only will you make a student feel more comfortable in the host country, you will enrich your own life.

Knowing Where to Stop

American hosts are not responsible for financial support nor, in most cases, does the student live with hosts. It is recommended that hosts never cosign for loans or subscriptions to services such as cellular phones. There are other areas of the student’s life, as well, which the host is not expected to handle. The international student adviser at the student’s school is knowledgeable about immigration regulations and consequently responsible for assisting students in the following areas.

-

Employment restrictions

-

Immigration and visa issues, including travel

-

Academic concerns with professors, advisers, and administrators

Hosts can be helpful in locating medical services or assistance for family or marital problems is the institution does not provide these services to international students. They can also help find apartments, purchase needed items, and provide practice in speaking English. If student ask you questions concerning major medical, financial, or other problems, always refer them to the international student adviser at the school. You may offer to attend the meeting with the adviser if you feel that would be helpful, but it is important for you to include the institution’s adviser in conversations about these issues.

Keeping in Touch

The return home for a student is one of the best parts. Not only does the student get to see their family and friends again, but the student will see his or her country with a new perspective. As a host, it is fun to see how a student changes and what the student says about life back home. We hope that a mutual lifelong friendship will be created. Students are open to hosting you in their home countries and returning what you have given them.

Thank you for offering to host an international student. We know that it will be a fulfilling and rewarding experience for all involved.

About the Authors

Sabrina Moss is international student advisor at Cascadia Community College in Bothell, WA. Wade Bird is admissions evaluator, Seattle University R. Michael Philson, P.., is executive director of international education at Wichita State University.

About NAFSA

NAFSA: Association of International Educators is the leading professional association promoting the exchange of students and scholars to and from the United States. For more information about NAFSA, visit www.nafsa.org

For additional copies of the original publication, contact NAFSA Publications at 1.866.538.1927

Editor: Lisa Schock, NAFSA Design and Production: Drew Banks, NAFSA Copyright 2006 by NAFSA: Association of International Educators Washington, DC.

All rights reserved. NAFSA: Association of International Educators 1307 New York Avenue, NW Eighth Floor Washington, DC 20005-4701 USA

*Note: While “United States” can easily be used to identify the United States of America, we still have not come up with an appropriate term to indicate residents/citizens of the United States. Because there is no one term that adequately conveys this concept, we use “Americans” throughout this text to refer to individuals who are natives or residents of the United States of America.